A collaboration between Stuart Parkin's group at the Max Planck Institute of Microstructure Physics in Halle (Saale) and Claudia Felser's group at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids in Dresden has realized a fundamentally new way to control quantum particles in solids.

Writing in Nature (“A chiral fermionic valve driven by quantum geometry”), the researchers report the experimental demonstration of a chiral fermionic valve – a device that spatially separates quantum particles of opposite chirality using quantum geometry alone, without magnetic fields or magnetic materials.

The work was driven by Anvesh Dixit, a PhD student in Parkin' group in Halle, and the first author of the study, who designed, fabricated, and measured the mesoscopic devices that made the discovery possible. “This project was only possible because we could combine materials with exceptional topological quality and transport experiments at the mesoscopic quantum limit,” says Anvesh Dixit. “Seeing chiral fermions separate and interfere purely due to quantum geometry is truly exciting.”

Quantum Geometry as a New Control Principle

Chiral fermions – quantum particles distinguished by their handedness – are central to topological quantum materials and promised applications in ultra-low-power electronics, spintronics, and quantum information. Until now, controlling chiral fermions has required strong magnetic fields or magnetic doping, which severely limits practical device concepts.

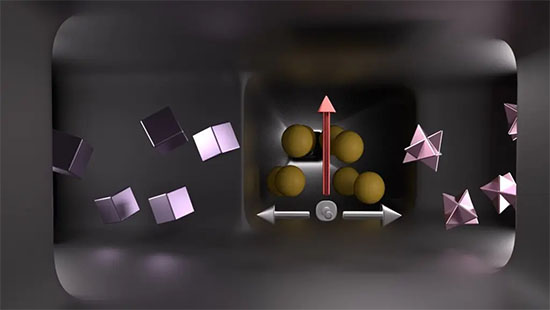

In this work, the researchers show that quantum geometry, a fundamental property of electronic wave functions, can instead be used as the control knob. High-quality single crystals of the homochiral topological semimetal PdGa, synthesized by Felser's group in Dresden, host multifold fermions with large and opposite Chern numbers. When an electric current is applied, the non-trivial quantum geometry of these bands generates chirality-dependent anomalous velocities. By micro-structuring PdGa crystals into three-arm devices, Dixit and colleagues demonstrated that fermions of opposite chirality are deflected into different arms, while trivial charge carriers are filtered out.

“This is a new electronic functionality,” explains Stuart Parkin. “Just as transistors control charge and spin valves control spin, this device controls fermionic chirality—a degree of freedom that has so far been inaccessible in electronics.”

Current-Induced Magnetization and Quantum Interference

The separated chiral currents were shown to carry orbital magnetizations of opposite sign, generated dynamically by the electric current itself. Crucially, these currents remain phase coherent over mesoscopic distances exceeding 15 micrometers.

Using a Mach–Zehnder interferometer carved directly from PdGa, the team observed quantum interference of chiral currents, even in zero external magnetic field – demonstrating coherent quantum transport of topological quasiparticles in a realistic device geometry.

“This beautifully illustrates how quantum materials can host entirely new device principles,” says Claudia Felser. “Here, quantum geometry replaces magnetism as the functional element.” Toward Chiral Quantum Electronics

The demonstrated chiral fermionic valve establishes three key capabilities:

Spatial separation of chiral fermions into Chern-number-polarized states

Electrical control of current-induced orbital magnetization, including its polarity

A tunable platform for quantum interference of chiral quasiparticles

Because the effect does not rely on magnetic fields, magnetic order, or electrostatic gating, it is broadly applicable to an extended family of homochiral and multifold topological materials.

The results open a pathway toward chiral quantum electronics, where information is encoded and processed using the handedness of quantum states.