The lithium-ion batteries that you find in many of your electronic gadgets, like your smartphone, typically consist of two electrodes connected by a liquid electrolyte. Apart from being prone to problems, including leakage, low charge retention and difficulties in operating at high and low temperature, this liquid electrolyte makes it difficult to reduce the size and weight of the battery.

Finding low-cost solid materials capable of efficiently and safely replacing liquid electrolytes in these batteries has been a considerable research interest over the past years.

Of the various types of solid electrolytes that have been developed so far, composite polymer electrolytes exhibit acceptable Li-ion conductivity due to the interaction between nanofillers and polymer.

Composite polymer electrolyte is typically a mixture of ceramic nanofiller and polymer electrolyte. The nanoscale ceramic fillers are known to be able to enhance mechanical or thermal stability as well as ionic conductivity of polymer electrolyte.

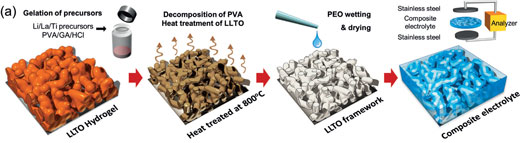

“Unfortunately, conventional composites suffer from agglomeration of nanofillers at high weight ratio which deteriorates the distribution of fillers and results in discontinuous ionic conduction pathways,” Guihua Yu , a professor in Materials Science and Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, at the Texas Materials Institute, University of Texas at Austin. “In our recent study, we fabricated a three-dimensionally (3D) interconnected framework consisting of ceramic nanofillers via an easy templating method using nanostructured hydrogels. The 3D ceramic framework can prevent aggregation of nanofillers and provide a continuous conduction pathway resulting in excellent ionic conductivity and stability. »

The conventional method for making composite polymer electrolytes is to physically mix nanoparticles with polymer electrolyte. The problem here is that the filler ratio is limited to only 10∼20wt%. At higher weight ratios the nanoparticles tend to agglomerate, resulting in deterioration of percolation and poor ionic conductivity.

“To solve this issue, we fabricated a pre-percolated network of ceramic filler instead of distributing particles in polymer,” Yu notes. “In our study, a 3D interconnected ceramic framework provides continuous pathways for ion conduction. We believe that our novel method will help to develop composite materials in a different but much improved way than conventional particle distributions. »

Discover